Installing software under a desktop OS should be a quick and easy task. Although systems such as pkgsrc—which build software from its source code—are very convenient some times, they get really annoying on desktops because problems pop up more often than desired and builds take hours to complete. In my opinion, a desktop end user must not ever need to build software by himself; if he needs to, someone in the development chain failed. Fortunately the two systems I’m comparing seem to have resolved this issue: all general software is available in binary form.

Ubuntu, as you may already know, is based on Debian GNU/Linux which means that it uses dpkg and apt to manage installed software. Their developers do a great job to provide binary packages for almost every program out there. These packages can be installed really quickly (if you have a broadband Internet connection) and they automatically configure themselves to work flawlessly in your system, including any dependencies they may need.

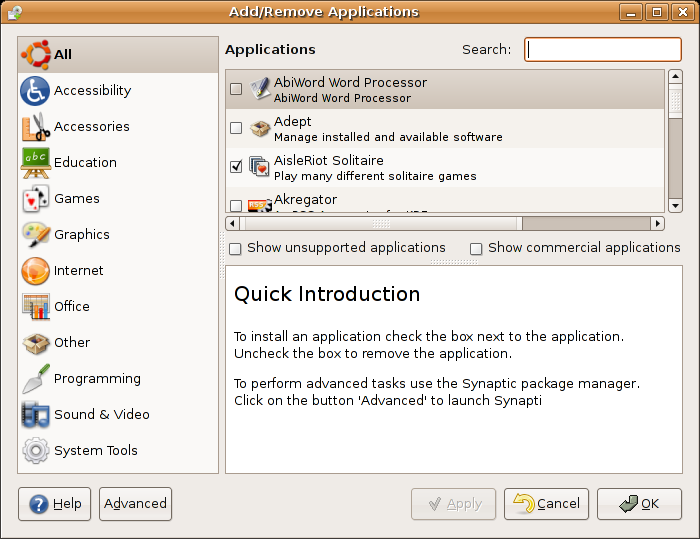

On the easiness side, Ubuntu provides the Add/Remove Applications utility and the Synaptic package manager, both of which are great interfaces to the apt packaging system. The former shows a simple list of programs that can be installed while the latter lets you manage your software on a package basis. After enabling the Universe and Multiverse repositories from Synaptic, you can quickly search for and install any piece of software you can imagine, including a few commercial applications. Installation is then trivial because apt takes care of downloading and installing the software.

Given that the software is packaged explicitly for Ubuntu (or Debian), each package morphs into the system seamlessly, placing each file (binaries, documentation, libraries, etc.) where it belongs. On a somewhat related note, the problem of rebuilding kernels and/or drivers is mostly gone: the default kernel comes very modularized and some proprietary drivers are ready to be installed from the repository (such as the NVIDIA one).

Unfortunately, you are screwed if some application you want to install is not explicitly packaged for the system (not only it needs to be compiled for Linux; it needs to be “Ubuntu-aware”). These applications are on their own in providing an installer and instructions on how to use them, not to mention that they may not work at all in the system due to ABI problems. I installed the Linux version of Doom 3 yesterday and I can’t conceive an end user following the process. The same goes for, e.g., JRE/JDK versions prior to 1.5, which are not packaged due to license restrictions (as far as I know). We will talk some more about this in a future post when we compare the development platform of each system.

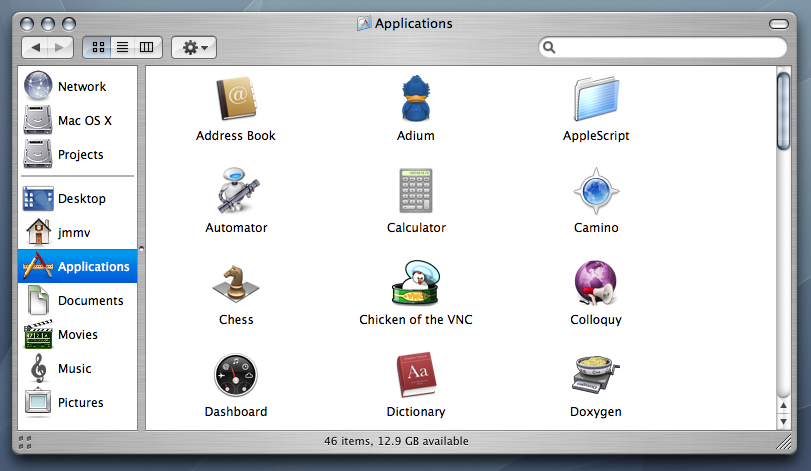

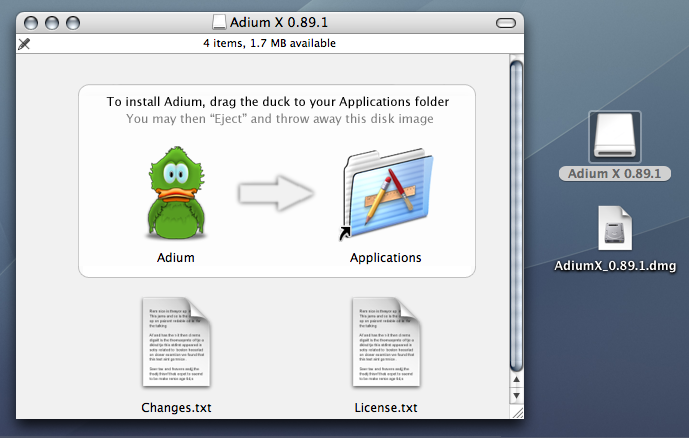

Mac OS X has a radically different approach to software distribution and installation. An applicaction is presented to the user as a single object that can be moved around the system and work from anywhere. (These objects are really directories with the application files in them, but the user will not be aware of this.) Therefore the most common way to distribute software is through disk images that contain these objects in them. To install the application you just drag it to the Applications folder; that’s all. (Some people argue that this is counterintuitive but it’s very convenient.) These bundles often include all required dependencies too, which avoids trouble to the end user.

Other applications may include custom (graphical!) installers, although all of them behave similarly (much like what happens under Windows). At last, some other programs may be distributed in the form of mpkgs which can be processed through a common installer built into the system; all the user has to do is double click on them. No matter what method is used by a specific program, its installation is often trivial: no need to resort to the command line nor do any specific changes by hand.

As you can see both systems are very different when it comes to software installation. If all the software you need is on the Ubuntu repositories, it probably beats Mac OS X in this area. But this won’t always be the case, specially for commercial software, and in those situations it can be much worse than any other system. I’m not sure which method I like most; each one has its own pros and cons as described above.