One of the things that often shocks new engineers at Google is the fact that every change to the source tree must be reviewed before commit. It is hard to internalize such a workflow if you have never been exposed to it, but given enough time —O(weeks) is my estimation—, the formal pre-commit code review process becomes a habit and, soon after, something you take for granted.

To me, code reviews have become invaluable and, actually, I feel “naked” when I work on open source projects where this process is not standard practice. This is especially the case when developing my own, 1-person projects, because there is nobody to bounce my code off for a quick sanity-check. Fortunately, this may not be the case any more in, at least, FreeBSD, and I am super-happy to see change happening.

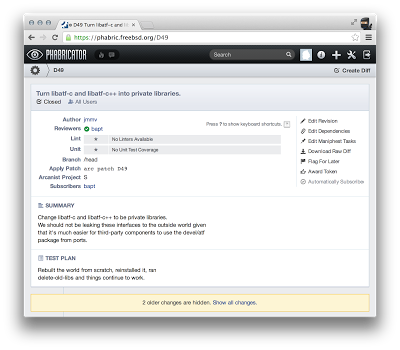

A few individuals in the FreeBSD project have set up an instance of Phabricator, an open source code review system, that is reachable at http://reviews.freebsd.org/ and ready to be used by FreeBSD committers. Instructions and guidelines are in the new CodeReview wiki page.

To the FreeBSD committer:

Even if you are skeptical —I was, back when I joined Google in 2009— I’d like to strongly encourage you to test this workflow for any change you want to commit, be it a one-liner or a multipage patch. Don’t be shy: get your code up there and encourage specific reviewers to comment the hell out of it. There is nothing to be ashamed of when (not if) your change receives dozens of comments! (But it is embarrassing to receive the comments post-commit, isn’t it?)

Beware of the process though. There are several caveats to keep in mind if you want to keep your sanity and that’s what started this post. My views on this are detailed below.

Note that the Phabricator setup for FreeBSD is experimental and has not yet been blessed by core. There is also no policy requiring reviews to be made via this tool nor reviews to be made at all. However, I’m hopeful that things may change given enough time.

Let’s discuss code reviews per se.

Getting into the habits of the code review process, and not getting mad at it, takes time and a lot of patience. Having gone through thousands of code reviews and performed hundreds of them over the last 5 years, here come my own thoughts on this whole thing.

First of all, why go through the hassle?

Simply put: to get a second and fresh pair of eyes go over your change. Code reviews exist to give someone else a chance to catch bugs in your code; to question your implementation in places where things could be done differently; to make sure your design is easy to read and understand (because they will have to understand it to do a review!); and to point out style inconsistencies.

All of these are beneficial for any kind of patch, be it the seemingly-trivial one-line change to the implementation of a brand-new subsystem. Mind you: I’ve seen reviews of the former class receive comments that spotted major flaws in the apparently-trivial change being made.

The annoying “cool down” period

All articles out there providing advice on becoming a better writer seem to agree on one thing: you must step away from your composition after finishing the first draft, preferably for hours, before copyediting it. As it turns out, the exact same thing applies to code.

But it’s hard to step aside from your code once it is building and running and all that is left for the world to witness your creation is to “commit” it to the tree. But you know what? In the vast majority of cases, nobody cares if you commit your change at that exact moment, or tomorrow, or the week after. It may be hard to hear this, but that pre-commit “high” that rushes you to submit your code is usually counterproductive and dangerous. (Been there, done that, and ended up having to fix the commit soon after for stupid reasons… countless times… and that is shameful.)

What amuses me the most are the times when I’ve been coding for one-two hours straight, cleaned up the code in preparation for submission, written some tests… only to take a bathroom break and realize, in less than five minutes, that the path I had been taking was completely flawed. Stepping aside helps and that’s why obvious problems in the code magically manifest to you soon after you hit “commit”, requiring a second immediate followup commit to correct them.

Where am I going with all this? Simple: an interesting side-effect of pre-commit reviews is that they force you to step aside from your code; they force you to cool down and thus they allow you to experience the benefits of the disconnect when you get back to your change later on.

Keep multiple reviews open at once

So cooling down may be great, but I hear you cry that it will slow down your development because you will be stuck waiting for approval on a dependent change.

First of all, ask yourself: are you intending to write crappy code in a rush or, alternatively, do you care about getting the code as close to perfect as possible? Because if you are in the former camp, you should probably change your attitude or avoid contributing to a project other people care about; and if you are in the latter camp, you will eventually understand that asking for a review and waiting for your reviewer to get back to you is a reasonable thing to do.

But it is true that code reviews slow you down unless you change your work habits. How? Keep multiple work paths open. Whenever you are waiting for a change to be reviewed, do something else: prepare a dependent commit; write documentation or a blog post; work on a different feature; work on a completely-separate project; etc. In my case at work, I often have 2-3 pending changes at various stages of the review process and 1-2 changes still in the works. It indeed takes some getting used to, but the increased quality of the resulting code pays off.

Learn to embrace comments

Experienced programmers that have not been exposed to a code review culture may get personally offended when their patches are returned to them with more than zero comments. You must understand that you are not perfect (you knew that) and that the comments are being made to ensure you produce the best change possible.

Your reviewers are not there to annoy you: they are there to ensure your code meets good quality standards, that no obvious (and not-so-obvious) bugs sneak in and that it can be easily read. Try to see it this way and accept the feedback. Remember: in a technical setting, reviewers comment on your ideas and code, not on you as a person — it is important to learn to distantiate yourself from your ideas so that you can objectively assess them.

I guarantee you that you will become a better programmer and team player if you learn to deal well with reviews even when it seems that every single line you touched receives a comment.

Selecting your reviewers

Ah… the tricky part of this whole thing, which is only made worse in the volunteer-based world of open source.

Some background first: because code reviews at Google are a prerequisite for code submission, you must always find a reviewer for your change. This is easy in small team-local projects, but with the very large codebase that we deal with, it not always is: the original authors of the code you are modifying, who usually are the best reviewers, may not be available any longer. FreeBSD also has a huge codebase, older than Google’s, so the same problem exists. Ergo, how do you find the reviewer?

Your first choice, again, is to try and find the owner of the code you are modifying. The owner (or owners) may still be the original author if he is still around, but it can be anyone else that stepped in since to maintain that piece of code.

Finding an individual owner may not possible: maybe the code is abandoned; maybe it is actively used but no single individual can be considered the owner. This is unfortunate but is a reality in open source. So do you abandon the code review process?

Of course NOT! Get someone with relevant expertise in the change you are making to look at your code; maybe they won’t be able to predict all of the consequences of the change, but their review is lightyears better than nothing. At work, I may “abuse” specific local teammates that I know are thorough in their assessment.

The last thing to consider when selecting your reviewers is: how picky are they? As you go through reviews, you will learn that some reviewers will nitpick every single detail (e.g. “missing dot at end of sentence”, “add a blank line here”) while others will only glance over the logic of the code and give you a quick approval. Do not actively avoid the former camp; in fact, try to get them involved when your primary reviewer is on the latter; otherwise, it’s certain that you will commit trivial mistakes (if only typos). I’m in the nitpickers camp and proudly so, if you ask.

Should all of the above fail, leaving you without a reviewer: ask for volunteers! There will probably be someone ready to step in.

Set a deadline

Because most committers in open source projects are volunteers, you cannot send out a change for review and wait indefinitely until somebody looks. Unless you are forbidden to commit to a specific part of the tree without review, set a deadline for when you will submit the change even if there have been no reviews. After all, the pre-commit review workflow in FreeBSD is not enforced (yet?).

If you end up committing the change after the deadline without having received a review, make sure to mention so in the commit message and clearly open the door at fixing any issues post-commit.

Learn to say no

Because code reviews happen in the open, anybody is allowed to join the review of a patch and add comments. You should not see this as an annoyance but you must know when to say no and you must clearly know who your actual approvers are and who are just making “advisory” comments.

Also note that comments in a review are not always about pointing obviously-wrong stuff out. Many times, the comments will be in the form of questions asking why you did something in a specific way and not another. In those cases, the comment is intended to start a discussion, not to force you to change something immediately. And in very few cases, the discussion might degenerate in a back-and-forth against two very valid alternatives. If this happens… you’ll either have to push your way through (not recommended) or find a neutral and experienced third reviewer that can break the deal.

Get to the reviews!

Wow, that was way longer than I thought. If you are interested in getting your code for FreeBSD reviewed — and who wouldn’t be when we are building a production-quality OS? — read the CodeReview wiki page instructions and start today.

And if you have already started, mind to share your point of view? Any questions?