I confess I am late to the game: the Go programming language came out in 2009 and I had not had the chance to go all in for a real project until two weeks ago. Here is a summary of my experience. Spoiler alert: I’m truly pleased.

The project

What I set out to build is a read-only caching file system to try to solve the problems I presented in my previous analysis of large builds on SSHFS. The reasons I chose Go are simple: I had to write a low-level system component and, in theory, Go excels at this; I did not want to use plain C; Go had the necessary bindings (for FUSE and SQLite); and, heck, I just wanted to try it out!

It only took me a little over two days to get a fully-functional implementation of my file system, and this is without having ever written a FUSE-based file system before nor any non-toy Go code. That said, I had previously written a kernel file system in 2005 and that helped navigating the whole endeavor and tuning the resulting performance.

Where is the code you ask? Nowhere yet unfortunately; I hope to make it available once it is ready.

The Go language review

The summary of what follows is simple: after two weeks, I’m in love with Go.

I remember languages people dismiss Go back in 2009 on the grounds that it was a simplistic language without novel concepts… but there lies its beauty: Go lets you get things done quickly and safely with few performance penalties. I feel I can write much more robust code with Go than with any other comparable language.

Disclaimer: Keep in mind that I’m still a newbie. I’m sure that some of the items below are naïve, incomplete or plain incorrect. If so, please let me know!

The good

Enforced coding style: You may or may not like Go’s coding style (I personally would change a few things), but the fact that it is chosen for you and that

gofmtexists beats any personal preferences you may have. No more thinking about tabs vs. spaces; no more thinking about brace placement; no more thinking about the look of your code. It. Just. Does. Not. Matter. Focus on your code’s logic and let the machine format it in a consistent manner across the whole Go ecosystem.Explicit error handling: Yes, the

if err != nil { return err }pattern gets old very quickly, but having to explicitly handle errors shows you how hard it is to write robust code.You’d say that C is similar in this regard, but not really. There are two key differences: the first is that Go functions can return more than one result, which makes it more difficult to ignore the error code if you want to use the actual result; and the second is the

deferkeyword, which helps avoid leaks in error paths. I personally prefer C++’s ability to implement the RAII pattern, butdeferis a good compromise.Do I miss exceptions? Not really. While exceptions let you keep your main code path clean of error handling, they also relegate error handling to a secondary place. This is OKish if the language has provisions to ensure that exceptions are handled at some point like Java’s

throwsdefinition, but that’s not how the majority of languages work. Just think of how easy is for exceptions leak all the way through the program’s entry point in C++ or Python.Strong typing, even for native types: The fact that the equivalent of C’s

typedefgenerates types that can’t be implicitly mixed, or the fact that numeric types are not automatically promoted to other types, is a good way to prevent subtle bugs. Having to explicitly convert among types forces you to think about the consequences of doing so: Integer overflow? Check. Sign issues? Check. Precision issues? Check.Builtin profiling with pprof: The pprof profiling tool was invaluable to diagnose performance and memory consumption deficiencies in my caching file system and the libraries I used. What’s best is that pprof was also incredibly easy to plug into my program.

Honestly, I’m in awe to see that this tooling is open-source because I’ve gotten very accustomed to this particular way of debugging at Google.

The standard library: While Go by itself is a decent language, it becomes excellent because of its extensive standard library. The existence of tooling to implement pretty much anything you want wins over any deficiencies you may think the language has. The same applies to Java, by the way.

Simple package management: Getting started with a piece of code is easy, and pulling in additional dependencies is trivial. I actually do not like the underpinnings of this “modern” trend of language-specific package management systems, but I must admit that it has been a pleasure to just add new imports, call

go get, and have everything up and running in a matter of seconds.Build speed: This item is not tied to my recent experience with Go but is worth mentioning. About two years ago, I built the Go language on my underpowered NetBSD VM. I was expecting horrendously long build times like those of GCC or Clang, but was pleasantly surprised to see that the Go compiler, along with its extensive standard library, compiled in a few minutes.

The bad

GOPATH: Sorry but having to modify the environment to get a program to run in the default case is ridiculous in this day and age: things should “just work” and Go is different. I have mitigated my concerns about this by writing aMakefilethat sets things up automatically so I do not have to worry about customizing my environment on a project basis.Package management: As we saw in the good parts, Go’s package management gets the job done but its views on the world are too simplistic. On the one hand, the development environment assumes that you will always want to use the

HEADversions of your dependencies; and on the other hand, the default is to merge the dependencies with your personal code in the same workspace.I’ve managed to work around the latter by splitting my dependencies in a separate directory and using

GOPATHto find them. The excellent article So you want to write a packaging system is a great resource on this topic, and as you read through it, you will realize that it’s geared towards revamping Go’s package manager.The simplistic

logmodule: It is good that the standard library provides a logging module, but it seems way too simple for anything other than trivial logging. Fortunately, the externalglogmodule provides increased functionality such as level-based logging and persistent logging. Therefore, you may say that being able to choose between something simple and something more complex is good, right?!Unfortunately, that’s not the case and this is the reason I pinpoint this particular module from the standard library. The real benefits of using

glogcome when the whole stack uses the same logging infrastructure and principles. Becauseglogis not the standard module, some Go packages will use it and others will not. As a result, you do not get the full benefits of usingglogin your project because most libraries you depend on will not do the same.Mutability by default (aka no

constkeyword): Before you say “hey,constis currently not present, but if we find the need for it later on, we’ll add it!”, that’s… not great. The problem with adding aconstkeyword post-facto is that this is the wrong keyword to add: state should be immutable by default, and what the language should have is amutablekeyword to clearly mark those variables that hold multiple values throughout their lifetime.The reason I point out this specific language feature is because I’ve mentally gotten very accustomed to separating constant vs. mutable variables in code. Reading code that adheres to this strict separation is easy to follow: you can quickly map the immutable state in your mind and then focus on the mutable pieces of the code to understand what’s happening. Without these clues, you need extra effort.

The ugly

Short identifiers: A lot of Go code, including the snippets in the documentation, is plagued by extremely short identifiers. Those are used as local variables, function arguments, method receivers, and even structure members. Combined with the heavy use of interfaces, it is hard to read the code: What’s a

c? And anr? And ans.wg? Yes, there is bad code all around, but when the official language documentation seems to recommend this approach, you can expect that others will follow the apparent recommendation in all cases.Remember that code is written to be read many more times than it is written. Fully spelled-out identifiers help significantly.

Maximum line length: Even though Go has a predefined coding style, there is no pre-specified maximum line length. While it is great to want to abolish a custom that remains from the punch-card days, keeping code narrow has its benefits: think of two or three side-by-side editors in a small laptop screen.

This would be a non-issue if editors were able to wrap long code lines in a way that made sense—just like word processors do with text—but current editors are terrible at this. So, personally, I will stick to the 80 character limit; I have given 100 a try per more modern recommendations… but when I opened the code in my laptop and couldn’t see two files at once without wrapping, I knew I had to go back to 80.

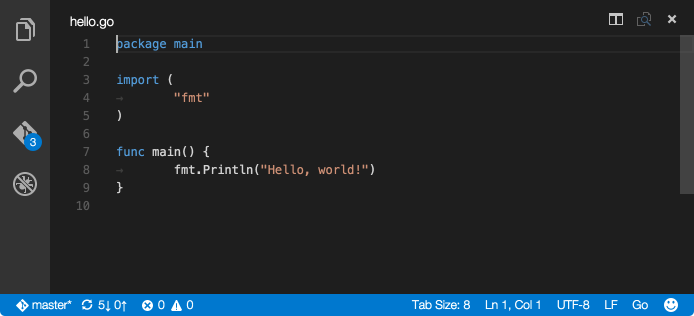

A note on Visual Studio Code

To conclude, let’s talk about editors. I’ve been a long-time Vim and Emacs user and now decided to give another editor a try. Heresy!

In fact, some time last year, I started playing with Atom after all the hype around this editor. It really is full-featured, but it also is overwhelming and fragile: overwhelming because there are knobs everywhere and fragile because I had never had an editor throw errors at me routinely during “normal” operation. (I’m sure I can blame some plugin I installed, but still.)

Soon after, Visual Studio Code (VSCode) came out: an open source editor from Microsoft no less. I installed VSCode just to take a look and I found much sought simplicity: just look at the way to configure the editor, which is by adding personal or project-specific overrides to an empty JSON file. I felt I’d enjoy this editor more than Atom though I did not have a use for it at the time: most of my development still happens over SSH so VSCode would not fit the bill.

This experiment with Go gave me the chance to use VSCode, particularly because I was writing the project primarily for OS X (my desktop) and because I wanted an IDE-like experience. As it turns out, VSCode has a pretty good Go plugin. The reason I wanted IDE integration is because writing code in an unknown language with an unknown standard library is a task that truly benefits from autocompletion and inline syntax validation. I wouldn’t have been able to prototype my file system as quickly as I did with a bare editor.

I know, I know, I could have set up Emacs to do the same thing, but I just wanted to give VSCode a ride. And, mind you, I just took a look at what’s involved to set Emacs up for Go and didn’t find it pleasing; way too much manual work involved.

Do you Go already?