In a recent work discussion, I came across an argument that didn’t sound quite right. The claim was that we needed to set up containers in our developer machines in order to run tests against a modern glibc. The justifications were that using LD_LIBRARY_PATH to load a different glibc didn’t work and statically linking glibc wasn’t possible either.

But… running a program against a version of glibc that’s different from the one installed on the system seems like a pretty standard requirement, doesn’t it? Consider this: how do the developers of glibc test their changes? glibc has existed for much longer than containers have. And before containers existed, they surely weren’t testing glibc changes by installing modified versions of the library over the system-wide one and YOLOing it.

So. What options do we really have? To answer this question, we need to look at how dynamic binaries work and what glibc is.

Static binaries

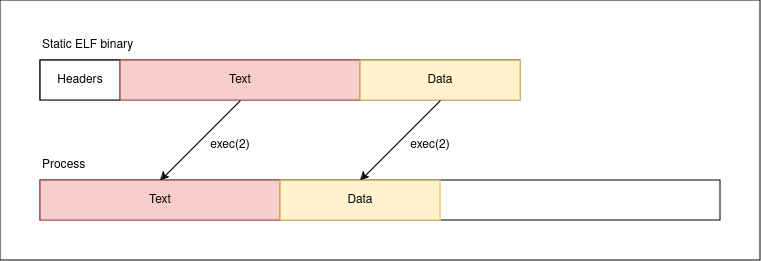

Static binaries are binaries whose program code is all contained in one executable. Such binaries can access system services via system calls—or else their utility would be minimal because they wouldn’t be able to interact with the OS—but their binary code is, in a sense, “complete”: what you see in the executable is exactly what gets laid out in memory for execution.

Here is how a sample static binary looks like. This is for a “hello world” program written in Go, which was the easiest thing to put together because Go is designed to bypass the C library almost everywhere:

$ file hello_go

hello_go: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, Go BuildID=2H_kXH_UFAOR5K6ibAke/aj_2VBvakhN2KujNxtMN/K5TtKP8HHiX65VdbA19s/KxdoZHQEiOxCEbwRE346, with debug_info, not stripped

$ █

In the above, note that file claims that our sample hello_go program is statically linked.

When we ask the shell to run this hello_go binary, the shell forks a new process and uses the exec(2) family of system calls to replace the running image of the process with the content of hello_go. And because hello_go is statically linked, the text segment of the binary is loaded verbatim into the process.

Dynamic binaries

Let’s compare the above to a dynamically-linked binary by looking at the same “hello world” program written in C and linked against glibc:

$ file hello_c

hello_c: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=feeb95b014ef8151780e23fc7ca15de0599f05df, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

$ █

Note that file now claims that our sample hello_c program is dynamically linked and, indeed, if we look at its libraries—quick reminder: don’t use ldd on untrusted executables!—we see that glibc (libc.so.6) is there:

$ ldd hello_c

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007f54f25aa000)

libc.so.6 => /lib64/libc.so.6 (0x00007f54f239b000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f54f25ac000)

$ █

But wait a second. There is more than just libc.so.6 in the output of ldd. In particular, there is this other /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 “library” and, if you pay close attention to the earlier output of file, you’ll note that it claims that this is an interpreter. Why is there an “interpreter” if we are running machine code?! Did they lie to us when they said C was a compiled language?

Not so fast, no. “Interpreter” in this case should be read as “loader”, but the “interpreter” word comes from the nomenclature of the ELF headers stored in the program:

$ readelf -l hello_c

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x401040

There are 13 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr

FileSiz MemSiz Flags Align

...

INTERP 0x0000000000000318 0x0000000000400318 0x0000000000400318

0x000000000000001c 0x000000000000001c R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

...

$ █

To understand what this interpreter thing is all about, we need to look at what a dynamically-linked executable is. In essence, the program code in the binary is not complete: the code contains “gaps” in it that need to be filled with references to portions of code supplied by other libraries before it can begin executing. We can peek into what these “gaps” are:

$ readelf -r hello_c

Relocation section '.rela.dyn' at offset 0x4c0 contains 2 entries:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000403fd8 000100000006 R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT 0000000000000000 __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.34 + 0

000000403fe0 000300000006 R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT 0000000000000000 __gmon_start__ + 0

Relocation section '.rela.plt' at offset 0x4f0 contains 1 entry:

Offset Info Type Sym. Value Sym. Name + Addend

000000404000 000200000007 R_X86_64_JUMP_SLO 0000000000000000 puts@GLIBC_2.2.5 + 0

$ █

readelf tells us that the hello_c binary has three different “relocations”: in other words, it has three different “gaps” that need to be patched at runtime with the address of the code that supplies those symbols. The program cannot run without those being filled in first. So if it cannot begin executing before those references are resolved, how does the program run?

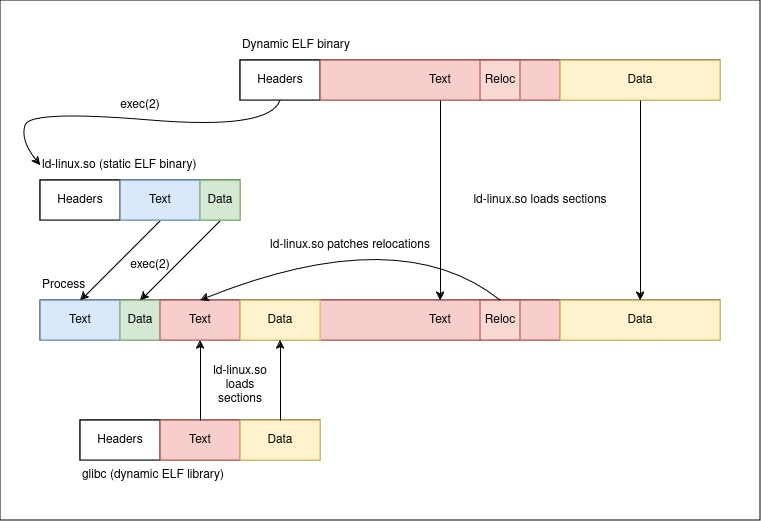

You might think that the kernel is somehow responsible for dealing with dynamic libraries, but that’s not the case. Dynamic libraries are a user-space concept and this is precisely where the interpreter comes into play.

When we ask the kernel to exec(2) a dynamically-linked ELF binary, the kernel loads the interpreter into the process image, not the code of the binary, and passes the path of the binary to the interpreter.

The interpreter, ld-linux.so in our case, is then in charge of setting up the remaining of the process by loading all required shared libraries into the process and then resolving relocations (“filling the gaps”) among them. In particular, the dynamic linker is the one that loads glibc into the process.

We can see that this is the case by asking the dynamic linker to print its own file accesses by setting LD_DEBUG=files:

$ LD_DEBUG=files /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 ./hello_c

75369: file=./hello_c [0]; generating link map

75369: dynamic: 0x0000000000403e08 base: 0x0000000000000000 size: 0x0000000000004010

75369: entry: 0x0000000000401040 phdr: 0x0000000000400040 phnum: 13

75369:

75369:

75369: file=libc.so.6 [0]; needed by ./hello_c [0]

75369: file=libc.so.6 [0]; generating link map

75369: dynamic: 0x00007f9aad868960 base: 0x00007f9aad682000 size: 0x00000000001f0b70

75369: entry: 0x00007f9aad6ac260 phdr: 0x00007f9aad682040 phnum: 14

75369:

75369:

75369: calling init: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

75369:

75369:

75369: calling init: /lib64/libc.so.6

75369:

75369:

75369: initialize program: ./hello_c

75369:

75369:

75369: transferring control: ./hello_c

75369:

Hello, world!

75369:

75369: calling fini: [0]

75369:

75369:

75369: calling fini: /lib64/libc.so.6 [0]

75369:

75369:

75369: calling fini: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 [0]

75369:

$ █

As a final note, see how I chose to invoke the dynamic linker explicitly—just as the kernel would do when asked to launch a dynamically-linked binary—instead of directly running hello_c.

Playing with glibc

OK, now that we know how a dynamically-linked ELF executable is loaded into memory, let’s play with glibc.

First, we download glibc, build and install it into a temporary directory like /tmp/sysroot/:

$ git clone https://sourceware.org/git/glibc.git

$ cd glibc

glibc$ git checkout release/2.40/master

glibc$ mkdir build

glibc/build$ ../configure --prefix=/tmp/sysroot

glibc/build$ make -j $(nproc)

glibc/build$ make -j $(nproc) install

glibc/build$ █

With that done, we should be able to use the new glibc. But…

$ LD_LIBRARY_PATH=/tmp/sysroot/lib ./hello_c

Floating point exception (core dumped)

$ █

Kaboom.

Indeed, as my coworker claimed, it doesn’t seem to be possible to load a different glibc at runtime than the one provided by the system. (YMMV. I got this to work on another system.) Looking at the stack trace of the core dump, we see:

Stack trace of thread 75841:

#0 0x00007f227d93903b n/a (/tmp/sysroot/lib/libc.so.6 + 0x15403b)

#1 0x00007f227d9f19f6 _dl_sysdep_start (ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 + 0x1c9f6)

#2 0x00007f227d9f335e _dl_start_final (ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 + 0x1e35e)

#3 0x00007f227d9f2048 _start (ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 + 0x1d048)

Our process is crashing within glibc as soon as it is loaded by ld-linux.so. The details of the crash are not interesting for our purposes, but can we do anything about them?

Playing with the dynamic linker

What’s more interesting is to peek into what’s shipped by glibc. We can do this by looking under the /tmp/sysroot/ hierarchy that we generated earlier and finding:

$ ls /tmp/sysroot/lib/

...

ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

...

libc.so

libc.so.6

...

$ █

There is a ton more stuff in there. But what’s important to notice is that the dynamic linker ships with glibc. The two are closely coupled, and using one without the other can lead to the kinds of crashes shown earlier.

And remember: as we saw above, it is possible to manually launch the dynamic linker. So if we do the following:

$ LD_LIBRARY_PATH=/tmp/sysroot/lib /tmp/sysroot/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 ./hello_c

Hello, world!

$ █

We don’t get a crash anymore. What’s even better is that we also seem to get what we expect without even setting LD_LIBRARY_PATH:

$ /tmp/sysroot/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 ./hello_c

Hello, world!

$ █

We should confirm that the previous invocation of hello_c is actually using our own glibc version and not the system-supplied one. To do that, we can strace the dynamic linker; it’s just a program after all:

$ strace /tmp/sysroot/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 ./hello_c 2>&1 | grep libc.so

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/sysroot/lib/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

$ █

Indeed, hello_c did use the newly-built glibc by “just” asking the newly-built dynamic loader to execute the binary.

To summarize, glibc ships both the ld-linux.so dynamic linker and the libc.so.6 shared library. The two are closely coupled. Running a binary against the C library without also using a matching dynamic linker can lead to crashes. But running a binary directly with a specific dynamic linker ensures that the binary picks up the matching C library.

Putting this to use

Alright, now that we know that it is actually possible to run a binary against a version of glibc that’s not the one provided by the system, we can try to solve the original problem we faced: running tests against a modern glibc.

One possibility is to modify the commands used to run the tests to prefix them by .../lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2. This could work but I posit is difficult to integrate with a test execution environment because we don’t necessarily control the commands that end up executing the test binaries.

Another possibility is to modify the way the tests programs are being built by supplying additional linker arguments—say, via the traditional LDFLAGS—to point the linker at a different interpreter with the --Wl,--dynamic-linker flag:

$ cc -o hello_c -Wl,--dynamic-linker=/tmp/sysroot/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 hello.c

$ strace ./hello_c 2>&1 | grep libc.so

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/sysroot/lib/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

$ █

Better. Now the built binary “knows” which glibc to use without us having to specify it explicitly every time we attempt to launch the program.

What if we aren’t building the binaries? What if we are just reusing a binary that already exists? patchelf to the rescue:

$ cc -o hello_c hello.c

$ strace ./hello_c 2>&1 | grep libc.so

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/lib64/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

$ patchelf --set-interpreter /tmp/sysroot/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 ./hello_c

$ strace ./hello_c 2>&1 | grep libc.so

openat(AT_FDCWD, "/tmp/sysroot/lib/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

$ █

Voila. We have modified an existing executable to use whichever glibc we desire.

Versioning glibc

But hold on a second. Can we use whichever glibc really? Is it actually true that glibc versions are completely interchangeable? Unfortunately not.

A binary built against an old version of glibc is guaranteed to run against a newer version of glibc without recompilation. But the counterpart is not true: a binary built against a new glibc may not run against an older glibc.

This poses a problem: how can we upgrade glibc across separate production and development environments? If we upgrade production first, binaries built in development environments will continue to work properly but developers may not be able to reproduce bugs found in production. And if we upgrade development environments first, the binaries they produce may be incompatible with production, leading to random crashes later on.

Here is an idea I’ve seen work in the past: let’s extend the sysroot concept presented above and version it!

We start with /usr/sysroot/v1/ which contains the first version of the core system libraries we have to support. All binaries that we build for production deployment are explicitly linked against the ld-linux.so of this directory, so they are always validated against v1 of the sysroot. v1 remains immutable, which means new builds of the binaries will continue to work as tested in the past.

Whenever we want to upgrade glibc, we create a new sysroot, /usr/sysroot/v2/. This new v2 is deployed to all environments (development and production) that may need to use the new glibc. This deployment step is risk-free because nothing is yet dependent on v2. After that, we proceed to rebuild all binaries that we want to test and run, this time pointing at the ld-linux.so within v2. Deploying these new binaries causes them to use the new version.

As long as the /usr/sysroot/ subdirectories remain immutable and synchronized across all environments in which binaries run, we are guaranteed to always get a deterministic version of glibc for a given binary.

That’s just a design sketch though. It may or it may not work for you. As I mentioned earlier, I’ve seen this work well in a large corporate environment before, but it introduces some extra complexity that you need to take care of.

What’s the moral of the story? Containers are, usually, not the best solution to a systems problem. While they might be coerced to deliver the desired results, they come with a heavy cost. Unix has been around for a long time and there exist alternate solutions to problems that don’t require full replicas of a functioning system. A ton of the bloat we face today in development tools and deployments comes from the abuse of heavyweight containers. So, every time you think “containers!”, pause to explore alternatives—you may find cheaper, more portable, and simpler solutions.

If you want to learn more about this and related topics, I’d recommend grabbing a copy of the classic “Linkers and Loaders” book. It’s old, but it’s still very relevant.