Or the more tired “One week with Claude Code”-type article.

It’s no secret that I’ve been grumpy about the new AI-based coding trend. I’ve been grumpy about the “push from above to use AI or else”. I’ve been grumpy about the eye-rolling hype I see on LinkedIn. I’ve been grumpy about being on the receiving end of vibe-coded PRs that over-engineer solutions to simple problems. I’ve been grumpy about the thought that we are about to see an amount of bloat like we have never imagined before.

But, at the same time, I’ve been using LLMs to review my articles, to perform deep research, to generate cover pictures, and before last week, I had even dipped my toes into AI-based coding agents to help me with boring, repetitive tasks. And you know what? I see their promise of increased productivity, yet the amounts of slop I’ve witnessed make me skeptical and I have had little experience with coding agents myself to judge their promised usefulness.

So… surprise! Last weekend I decided to start a Claude Code subscription and, after spending a week on it, I am uncomfortably excited to use it more. How has this happened? Let’s take a look at how I ended here, the kinds of mini-projects I worked on throughout this past week, and the (semi-expected) downsides I encountered.

It’s sad to have to say this, but this article was hand-written. Yes, despite the em dashes. Subscribe to show your support!

A blog on operating systems, programming languages, testing, build systems, my own software projects and even personal productivity. Specifics include FreeBSD, Linux, Rust, Bazel and EndBASIC.

How did I get here?

Over the course of last year, I was exposed to multiple vibe-coded PRs and was not impressed. Those PRs came with unnecessary features, code duplication and improper abstractions, useless comments littered throughout, and useless “change-detector” tests. Reviewing these PRs was a lot of effort for me and pushing back on obvious bugs was exhausting.

But coding agents are all the rage today and I’m being… let’s say… strongly encouraged to use them. So I dipped my toes in with Gemini CLI for a little bit. (Why not Claude Code? Easy: because it doesn’t offer a free tier whereas Gemini CLI does.) During this early trial period, I restricted myself to relatively simple and boring changes like “fill in these tests” or “help me fix this algorithm that doesn’t quite work”—and it delivered. However, any attempts at asking for more complex changes usually went haywire for me.

Now, during the last few weeks, I’ve been rewriting the core interpreter of EndBASIC; all of it by hand. This is the kind of work where I just cannot trust AI (yet?) to generate efficient and minimal code. But, as I approach the “last bits” of the core foundations, what’s left to do is kinda boring. It’s repetitive, but not the kind of code that can be abstracted behind functions. And it’s straightforward once the underpinnings have been figured out.

So… after being nudged to use Claude Code over, and over… and over again… I finally gave in and, just a week ago, I decided to pony up and get a Pro subscription to toy with it in my side projects.

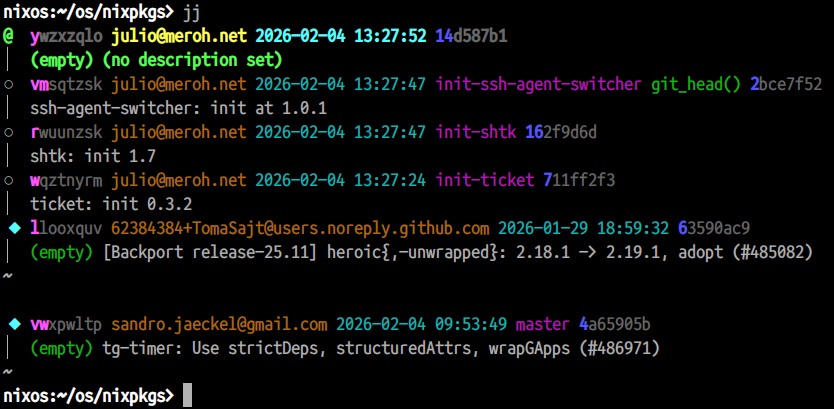

Dipping my toes in nixpkgs

Right when I decided to give Claude Code a go, I also decided to try NixOS. The trigger for this was an article on using micro VMs to isolate Claude Code. Installing NixOS was easy but after setting it up, I was missing a couple of packages. This was the perfect opportunity to give Claude Code a “meaty” task for something I was too lazy to do by hand: the nixpkgs language isn’t famous for being easy to work with, and I could live without those packages just fine, but having them around if possible would be “nice to have”.

Note that I’m not new to the software packaging world. I spent years creating and maintaining packages for NetBSD and I also managed a couple of RPMs for Fedora. So, even if nixpkgs’ syntax was completely alien to me, I could reason about the semantics of the vibe-coded packages. Consequently, even when Claude Code was really confident about its creations, I knew I had to iterate on them a little. By now I feel like I have some reasonably decent PRs (one for ticket—more below—and one fo ssh-agent-switcher) to merge upstream, but as we’ll continue seeing throughout this experience, the human iteration part that followed the initial code dump was critical to obtain high-quality results.

Supercharging EndTRACKER

I then looked at EndTRACKER—my poorly-named dynamic blog service—and thought… hey, I haven’t touched this project in a long time and there are a few important features and large-scale code changes I’ve been wanting to do in order to make it public. What if I used it as a playground for agenetic coding?

I started by asking Claude Code to write a “delete comment” feature for comment moderation. This required implementing a new REST API—a truly boring and tedious thing to do at this point—and figuring out the UI. My first prompt was rather poor in retrospect, but given how many other APIs exist in the code base and the fact that the UI is standard Vue.js, Claude Code pretty much one-shotted the implementation. I had a long-desired feature in my hands in basically minutes.

Next, I wanted to do something trickier: I wanted to prune anything that resembled PII from the database. In particular, I wanted to eliminate the literal user agent strings and replace them with more general data points about them (browser / OS pairs). This was not a hard change to do by hand, but it required dealing with a new dependency I was not familiar with, implementing new database hooks, updating business logic, and creating a throw-away migration script.

And this is where things got interesting. My first prompt was way too under-specified, but I got back a change that seemed OK. I tried to salvage it with manual iteration but soon concluded that I had to start over. After all, Claude Code spent like 5 minutes creating code so… don’t get too attached to any changes it makes! I wrote a new prompt, this time much more detailed, and clarified various “mistakes” I had seen in the first implementation.

At this point, I instructed Claude Code to generate a plan, and at each step during execution, to create a new commit, to update tests, and to run them all. Claude Code churned along for a while and produced about 8 different commits for the various implementation phases. And these 8 commits looked nice: their descriptions made sense, the changes were lint-free, well-formatted, and with good docstrings, and there was new test coverage.

Peeking under the covers

But… individually, these separate “small changes” were pointless because the boundaries between them were meaningless. Furthermore, as I started reviewing the diffs in detail and playing with the results, I started encountering deficiencies: unnecessary code and features that I did not ask for, incomplete logic, misplaced and duplicate code… It took about 7 more iterations (and therefore 7 more prompts and commits) to work with Claude Code to come up with a decent change. By then I was pretty happy with the combined result so I squashed all 15 commits into one and shipped the feature.

The above is important to highlight though. The original vibe-coded result was not of the quality I would expect. I had to do deep thinking work to simplify the implementation, remove fluff, and to make it efficient (even if the changes were via prompts). And at no point did the 15 commits leave my machine: to an outsider, all I did was write just one PR—but it’d have been trivial for me to inflate numbers at the expense of my reviewer’s time and CI costs if I needed to (hint: be careful with what you measure).

So far so good though. This sort of iteration was more interesting than I expected.

The really cool bit came soon after when I asked Claude Code to produce a throw-away migration tool to deconstruct the user agents and store their basic data points in separate columns. I gave it access to the test database and… it pretty much one-shotted the tool. As a migration tool, I couldn’t care less about the maintainability of the code because I would delete it immediately after-the-fact, so this was just a perfect use of time. And what was even cooler is that, once I found that the tool was too slow when I ran it on the real dataset, I asked Claude Code to parallelize a specific loop using async primitives and just a couple of minutes later I had an optimized version.

Why did I say cooler though? Because if I had written this tool by hand, the trade-off between letting the unoptimized version churn for ~30 minutes vs. spending time to make it parallel and rerun it was not obvious. But with the agent, I had a fixed version in under 2 minutes so I did actually save more than 20 minutes of my time.

Prototyping a “difficult” idea at work

The next thing I did late last Friday evening was debunk a claim from a peer that implementing an idea I proposed was “the nice solution that would take 6 months to implement”. I suppose I failed to communicate my idea in textual writing because while the proposal could certainly become complicated and a multi-month project, the basic implementation would really be a ~200 SLOC script.

And then it hit me… the idea is actually simple. So… why can’t I vibe-code the solution to show it in practice, instead of trying to describe and argue about hypotheticals? And indeed so. I spent about 20 minutes writing a detailed prompt with examples and expected results—aka a mini design doc—and fed it to Claude Code for planning and implementation. And voila: 10 minutes later I had a tangible script to demonstrate what I was proposing.

Note that 20 minutes composing an initial prompt is a longer time than I expected coming into this experiment. But as I get more experience communicating intent and getting a feeling for what works and doesn’t, it really does take time to write down desired changes in a way that allows the AI to come up with a reasonably-good solution upfront.

Toying with elisp

Lastly, and during this same time period, I also started using the ticket tool to track tasks for the agent. Now, ticket itself is OK: it’s a trivial tool to manipulate text files that represent tickets. But… as I worked with it more, I was missing some sort of integration with Emacs. So, hey, why not ask the agent to vibe-code an Emacs package for it? I can read LISP but I cannot easily write a plugin from scratch without a significant investment in learning.

And you guessed it: the agent gave me a ticket.el in just a few minutes, and it did exactly what I wanted with zero drama. I had to iterate on it because, while it worked, I wanted more features as I played with the results… but it was awesome to witness that I could build this integration “for free” as I would just not have done it at all otherwise.

Impressions

What can I say. This week’s experiences have left me wanting to use Claude Code more, not less. I’ve done a bunch of things that were just out of reach due to my lack of prerequisite knowledge. I’ve been able to do significant changes that I had postponed for years because those changes were mechanical and not exciting to execute on.

The key insight may be that I was able to do all of the above even when my energy was low. This week had been incredibly draining due to a work-related summit so my interest in coding “in the evenings” was just not there. But prompting Claude Code to get started was so frictionless that it was enough to get me started. It really feels like gaining a superpower; and for things that are low stakes or not novel, it’s perfectly fine.

But… it’s not all roses. The risks of vibe-coding are even more obvious to me than they were before. Creating convincing slop and gaming productivity metrics by producing more code and more PRs than ever is way too easy—and if those metrics become targets (as will inevitably happen), then slop is what we’ll get. Beware that just because we now can create something doesn’t mean we should: all code comes with significant maintenance costs, and those need to be evaluated.

Reflecting back on this experience, it was genuinely difficult to produce solid changes that I was proud of and that didn’t carry performance problems, code duplication, or obvious breakage. I had to review the outcome of the AI various times and slowly iterate on it to turn it into production-grade code. A better initial prompt would have steered the results to a better place, but I’m not convinced the output would have passed my quality bar anyway.

I’m not ready to buy into the “let agents loose on a project” trend. I see what these agents produce at scale when left unattended and… I’m terrified. Yes, they generate convincing and functional pieces of software like a web browser, a C++ compiler, or a ticket tracker… but when you start peeking under the covers, you realize that the browser has 3MM lines of code even when it uses Servo (a browser engine!) under the hood; the C++ compiler is slow and unoptimized; and the ticket tracker brings machines to a halt with its 300K SLOC. If we had ever complained about software bloat, we can’t comprehend the amount that’s coming.

Anyway. Did I code less during this first week with Claude Code? You know, I’m not sure. I definitely typed less code, but I still had to put in the work to review and adjust it to my liking. So it’s not 100% clear to me that I was more “productive” with the AI than without on a real feature. That said, it’s true that I got more different things done. At the end of the day, coding agents are tools to add to your tool belt, not to wholesale replace it.

Who knows, maybe this will change with better models, or maybe we have plateaued. For now, though, I’m excited to play with this stuff more.